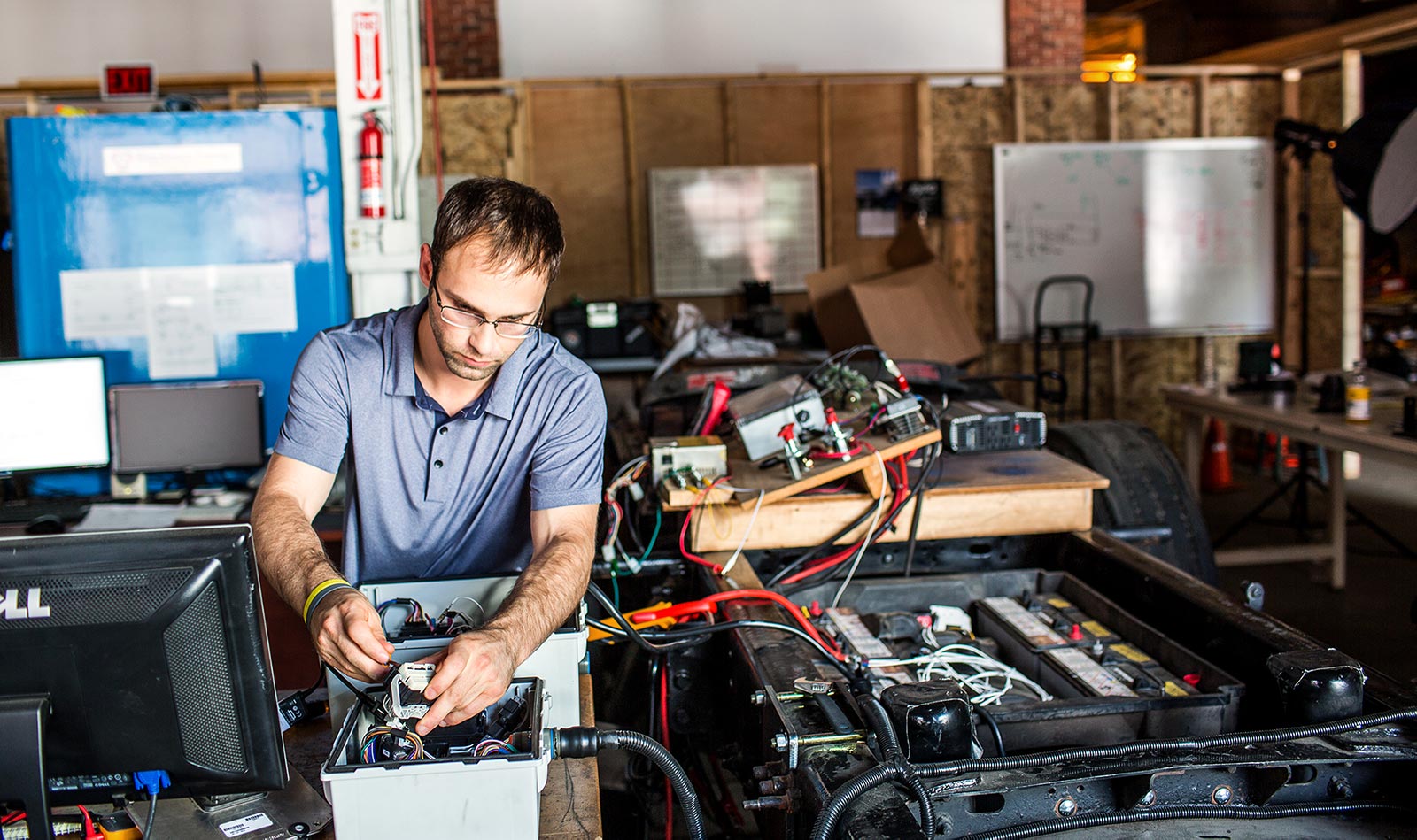

A Q&A with the Blackburn Energy Team, founder and creator, Andrew Amigo, president, Peter Russo, and engineer, Craig Nathan.

A Q&A with the Blackburn Energy Team, founder and creator, Andrew Amigo, president, Peter Russo, and engineer, Craig Nathan.

At CI Works, a collaborative workspace in Amesbury, one entrepreneur is walking in the footsteps of another. It’s safe to say, the entrepreneurial spirit has never left the building. Here you’ll find Andrew Amigo, modern-day visionary, founder and CEO of Blackburn Energy, occupying the same space as the acclaimed inventor of the Bailey electric car, Colonel Edward Bailey. They’re over a century apart from one another, but both share the same pursuit: harnessing the power of electricity.

In this exact building, Bailey set in motion the production of what would be the Bailey Electric Phaeton and successfully launched the car in 1907. Powered by a Thomas Edison battery, the car was reliable, silent, easy to ride, claimed no repair bills and could travel 100 miles on one charge — an eye-opener for its time and less of a hassle compared to gasoline vehicles.

Bailey discovered the potential in electric vehicles, now trending at full charge in the auto industry. Today, Andrew is using electricity for more than a power source but as an aid that can help change the landscape of the trucking industry. And his company, Blackburn Energy believes that providing low-cost technology that enables people to produce power can and will change the world for the better.

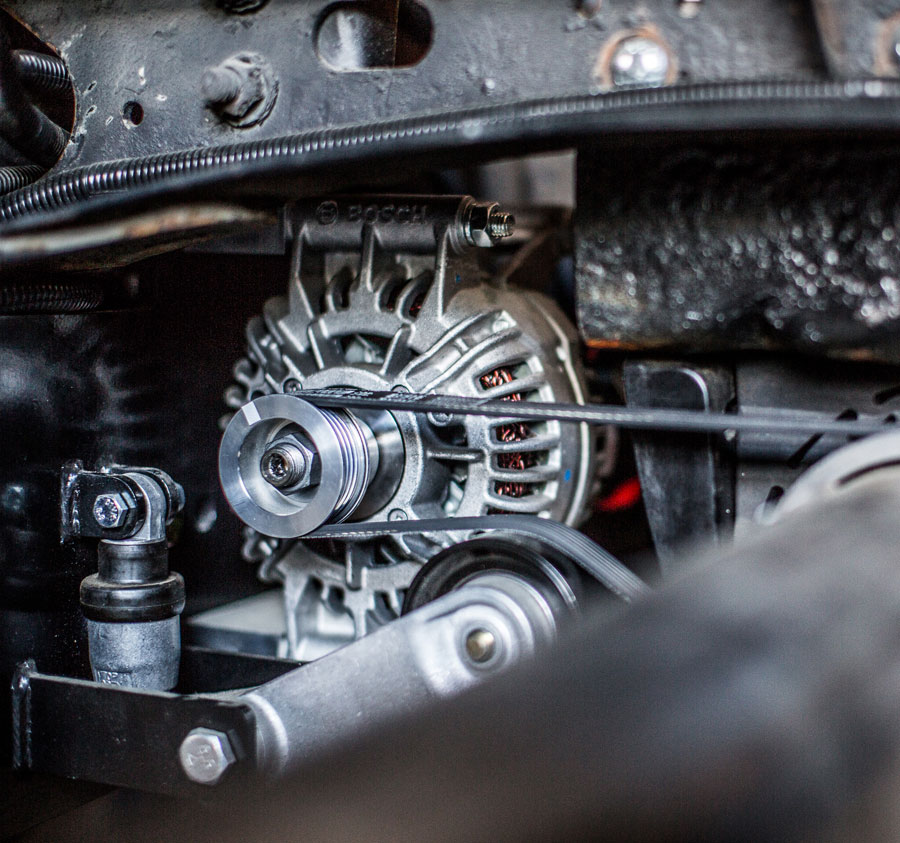

Their first product, RelGen (Renewable Electric Generation), addresses the increasing need for inexpensive clean and “quiet” electric power in long-haul sleeper trucks. RelGen is the only charging system that can fully charge four batteries in under four hours. This results in enhancing driver comfort, while increasing fuel efficiency, reducing maintenance and resulting in a reduction of up to 17 tons of carbon per truck per year by helping to eliminate overnight idling.

In the U.S. alone, 80% of all products are delivered on long-haul trucks. This requires over 650,000 truck drivers to sleep approximately 250 nights in their truck cabs – idling their trucks overnight. To make the challenge worse, 30 states have adopted no-idling while parked laws. Idling is the primary method for powering air-conditioning and charging batteries while parked overnight.

Blackburn’s ‘RelGen System’ is a kinetic energy recovery system. This means it captures the energy that is usually wasted during braking, idling or gliding and stores it in a series of batteries. After a long day on the road, the driver can use 5 kilowatts of electricity created from their ‘RelGen System’. Truckers can live their lives off that power and protect the planet in the process.

We recently sat down with the Blackburn Energy Team at their shared office space at CI Works in Amesbury. Asking them about what it’s like working in a startup, the challenges of the small business model and how working in the Merrimack Valley has helped them grow their business.